In the calm before the possible storm, it doesn’t look like courts will decide the election

But that outsized attention on courts may be misplaced. The discourse “feels like lawyers and courts are deciding the election and not voters. I don’t think that’s true,” said Justin Levitt, an elections law specialist at Loyola Law School. “There’s a feeling of anxiety in 2020 that has translated to an anxiety about the degree to which lawyers and courts will be controlling the election … Welcome to 2020. Anxiety level is high, period.”

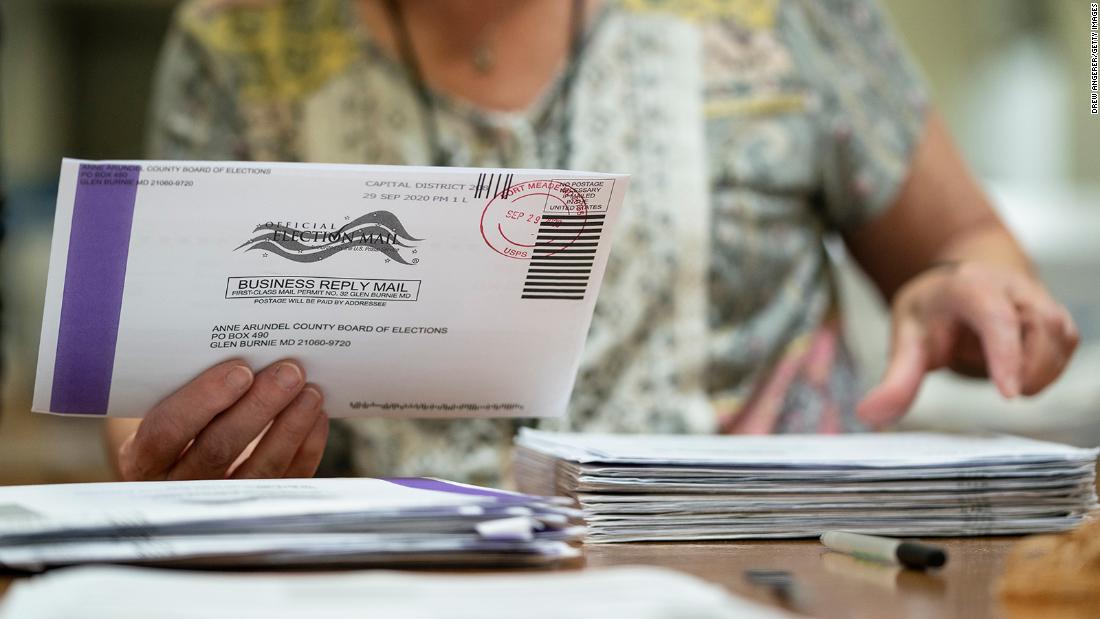

A handful of lingering court cases could still test how mail-in ballots get counted or are thrown out in some states, especially if the ballots have issues, such as illegible postmarks or signatures or were mailed on or near Election Day.

But even with Barrett’s confirmation likely next week, which would shift the balance of the high court further to the right, the actual impact that ongoing voting litigation may have on the presidential election before Election Day is little.

Less than two weeks before November 3, the cases still kicking around court are largely about which mail-in ballots will be counted if they arrive to officials late — the same types of rules that are typically disputed before and even after an election, said Jonathan Diaz of the Campaign Legal Center, a voting access litigation group.

“The average voter doesn’t pay much attention, if any, to the vagaries of litigation,” Diaz added.

“The first prayer of the elections administrator is, ‘Please, God, don’t let it be close,'” Steve Vladeck, a CNN legal analyst and law professor, said this week. “And that’s increasingly the prayer of the elections lawyer as well.”

2020’s hanging chad?

So will ballot postmarks be the issue that could throw this election into chaos later, like the hanging chads on Florida ballots in 2000?

Sophia Lin Lakin of the ACLU’s Voting Rights Project called that the million-dollar question. “It’s hard to anticipate what might be the subject of a challenge, in terms of counting,” she said.

For there to be election chaos in court, the vote would have to be extremely close in one or two key states for the courts to weigh in. And before Election Day, federal courts have repeatedly stayed away from changing states’ voting procedures that are already in practice.

“It’s all probabilistic. If Pennsylvania is not the tipping point, this won’t matter,” Vladeck said, about the Supreme Court’s 4-4 split over the Pennsylvania case. “Imagine Pennsylvania is within 3,000 votes. Nothing that the Supreme Court did settles whether those ballots would be counted.”

But while that issue and questions over how elections officials review signatures on mailed ballots still linger in courts, any and all issues about ballots could become post-Election-Day legal fodder in a close election.

Hanging chads became emblematic of the court battle in Florida for the 2000 election. Yet they were only one topic of a raft of ballot-counting questions disputed in the Bush v. Gore election.

There’s a major difference between a close election where litigation won’t swing the result and one where it could, Levitt added. “Just because there’s a payout in Vegas for a national royal straight flush, doesn’t mean it will happen twice,” he said.

The Supreme Court factor

In a few key states, vote-counting rules still are being disputed in court.

One appeal from Wisconsin is currently pending before the US Supreme Court, over whether mail-in ballots must be postmarked by Election Day, as is currently the case.

Vladeck said the Pennsylvania decision — with Chief Justice John Roberts joining the court’s liberal-leaning wing to deny a Republican Party attempt to override the state’s plan on receiving ballots three days after Election Day — was “a sign that the chief is going to sit on his hands” before Election Day, inclined to adhere to an approach for courts not to disrupt elections officials and voters.

But the high court’s inaction still could set up another round for later, if litigation over another state’s vote-counting brings the question of how to count late-received ballots, with Barrett as a tie-breaker.

The Senate could vote to confirm her before Election Day.

“There’s this specter that the same issues will come back,” Vladeck said. But as of now, he added, it looks like there will be calm in court.

![]()